Photos by: Doi Ka Noi

Photos by: Doi Ka Noi

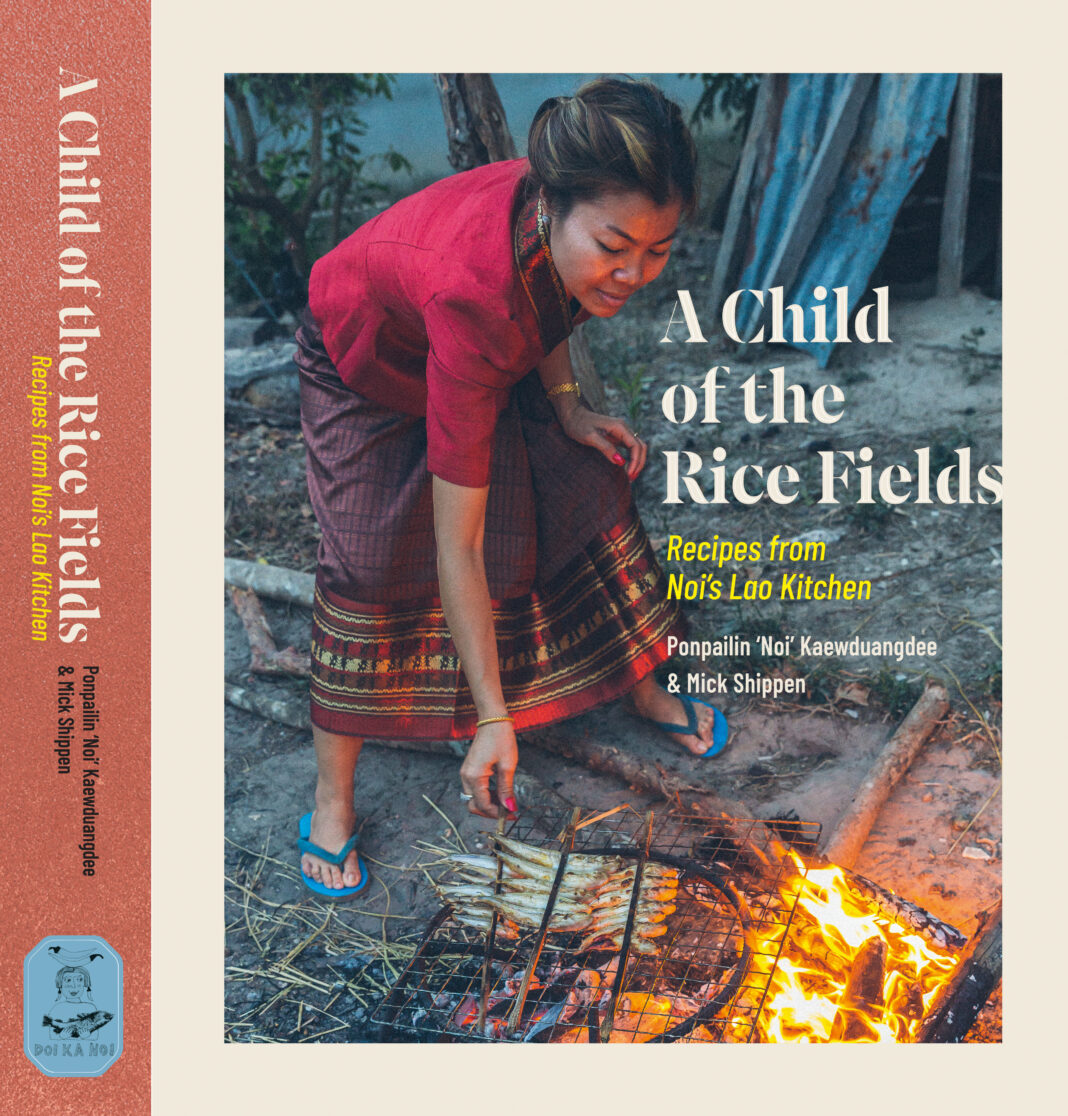

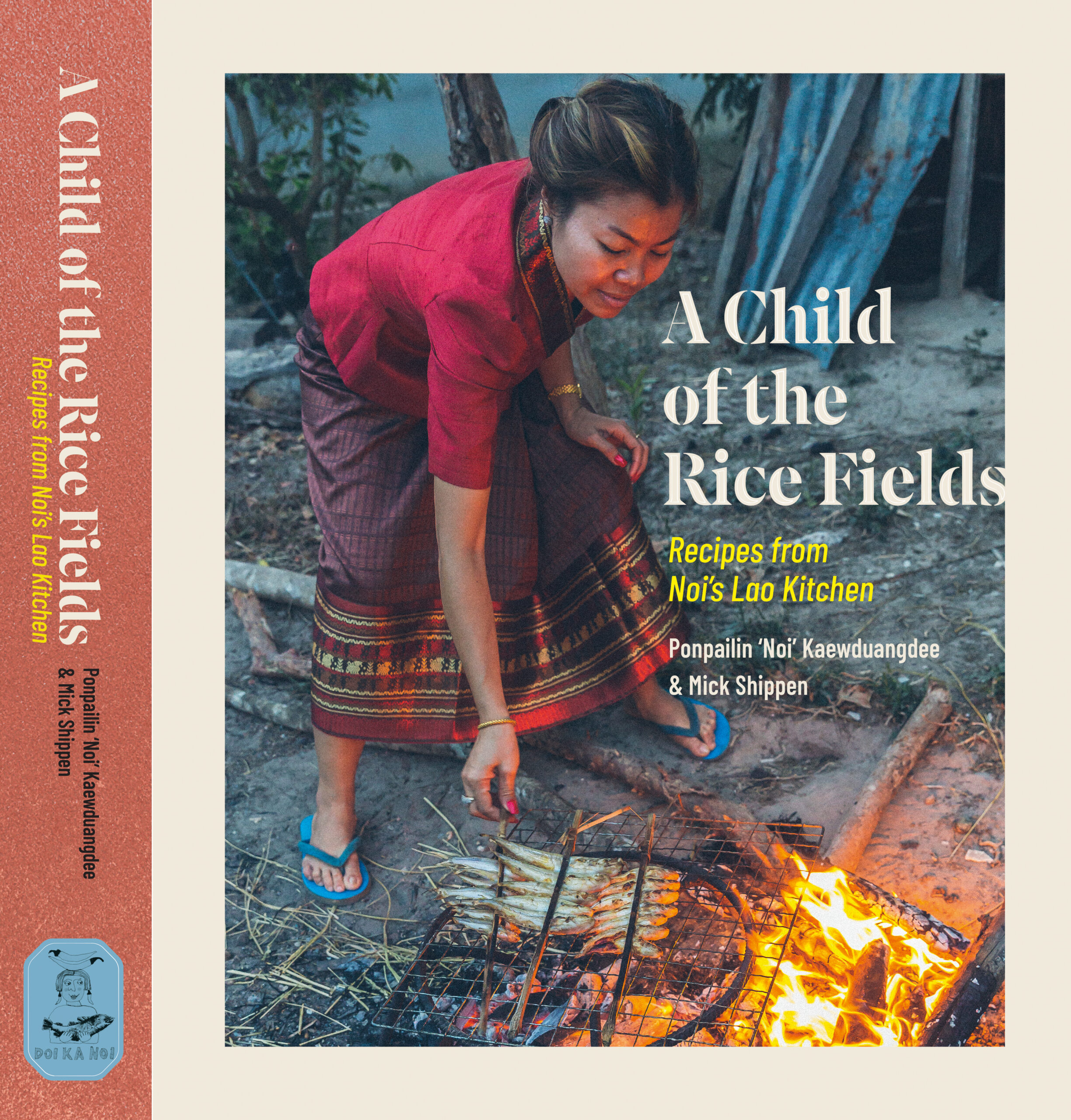

Celebrated chef Ponpailin Kaewduangdy, known as Noi, has captured the essence of traditional Lao cooking in her new book ‘A Child of the Rice Fields: Recipes from Noi’s Lao Kitchen.’ As the chef and proprietor of Vientiane’s renowned restaurant Doi Ka Noi, she’s spent years championing authentic Lao cuisine. Champa Meuanglao sat down with her to explore her journey from the rice fields of Khammouane Province to becoming one of Laos’ most influential culinary voices.

Can you give us a little background about your restaurant, Doi Ka Noi?

I opened my restaurant, Doi Ka Noi, in 2017. I was compelled to do so because it was difficult to find good Lao food in Vientiane restaurants. They all offered a similar and limited repertoire of standard dishes that were not representative of the food and flavors from my childhood. Nor did they showcase the incredible diversity of seasonal ingredients and the dishes that can be created with them. From day one, my cooking at Doi Ka Noi has focused on fresh, seasonal, and regional Lao dishes as part of a small weekly changing menu.

What inspired you to write A Child of the Rice Fields and share your recipes with the world?

My husband is a writer and photographer, so it was the perfect collaborative project. The initial idea was simply to write down and document the recipes I inherited from my grandmother, but it grew into a major 480-page book with 125 recipes and 400 images.

How did growing up in a subsistence farming community in Khammouane Province shape your perspective on food and cooking?

Subsistence living necessitates an understanding of the natural rhythms of sow, tend, reap, and preserve; how to care for livestock; catch, kill, and process fish and game animals; and a wealth of inherited knowledge about foraged leaves, shoots, fruits, and vegetables. Today, I still use market-fresh seasonal produce at home, and it shaped the Doi Ka Noi philosophy. I must say, however, that I am deeply concerned about how the diet of most people in Laos has changed and how it is affecting their health.

Can you share a special memory of learning to cook from your grandmother that influenced the book?

My grandmother had a reputation as a talented cook, but she had a stern character. Everything had to be done her way. There were no shortcuts. Under her watchful eye, I helped prepare every meal we ate, learned to build flavor in dishes using few ingredients, and over the years absorbed an incredible wealth of knowledge. As in all traditional kitchens, nothing was measured or written down. I was taught to taste and taste again, to adjust the seasoning with care, and to use my intuition.

My grandmother has long since passed on, but she left me with a deep understanding of my food culture. The food I prepare every day of my life is a tangible memory and a celebration of my love for her.

What do you think makes Lao cuisine unique, and why do you believe it remains relatively unknown?

Defining the food of a country that is home to more than 50 ethnic groups is an almost impossible task! The key tastes in Lao cuisine are spicy, salty, savory, sour, and bitter. There’s also an element of earthiness and woodsy flavors in some dishes. Sweetness barely gets a look-in. Often the cook’s job is to harmonize these flavors. But not always. Sometimes one or two are allowed to dominate. Cooking over charcoal, steaming or grilling in banana leaves, and the use of river fish and foraged ingredients also contribute to the unique character of the food. People will often say the core components are pa daek or sticky rice, but that is not universal. Many ethnicities do not use either.

How do you incorporate foraged and seasonal ingredients into your recipes, and what challenges or opportunities does this present?

Seasonality is important to me, as are foraged ingredients. Most restaurants will not feature these ingredients because they are usually only available in small amounts and a consistent supply can be difficult. I get around this with a weekly changing menu. The restaurant is only open from Friday to Sunday. Basically, I decide on the menu on Thursday after seeing what is available in the market that day.

Which dish from the book are you most excited for readers to try, and why?

Goy pa is a classic spicy Mekong fish and herb salad, and arguably the most loved dish in Laos, so definitely try that. But I would say take a deep dive into the world of jaews – extensive family of dips, sauces, and pastes used to enliven simple meals of sticky rice, grilled meats and fish, and steamed vegetables, often with an assertive punch of chili. One of my favorites is jaew mak kok, grilled hog plum jaew, and jaew khai tom, boiled egg jaew. There are 20 or so jaew recipes in the book.

You’ve mentioned that the book only touches the surface of your knowledge. What aspects of Lao cuisine do you feel are still waiting to be discovered by the wider world?

I am fascinated by the regional and ethnic minority foods of the north, be it Tai Dam, Tai Lue, Lanten, Haw Chinese, and others. At Doi Ka Noi, I regularly feature some of the dishes I have learned on our travels, and these will be the focus of our next book. I must confess to feeling a sense of urgency in the task as lifestyles are changing fast and knowledge is not being passed on like it used to be. It’s important to document the recipes.

“A Child of the Rice Fields: Recipes from Noi’s Lao Kitchen” is available at Doi Ka Noi restaurant in Vientiane. It has already been nominated in two categories in the 30th Gourmand World Cookbook Awards which will be held in Lisbon in June.

ລາວ

ລາວ