A walk through the Pearl of the Orient

Text by Anita Preston

Photos by Anita Preston / Evensong Film

A metropolis of around ten million people, Saigon is sprawling out and up rapidly. The downtown area has a dramatic cityscape. Colonial buildings rub shoulders with modern glitzy skyscrapers, and air-conditioned malls sit beside dank alleys with old ladies huddled over bubbling woks cooking spring rolls. Cobblers patch shoes with glue on the pavements, and top-brand athletic shoe shops are selling their wares down the street. The present firmly stamps its foot, but the past stands stubbornly in the shadows.

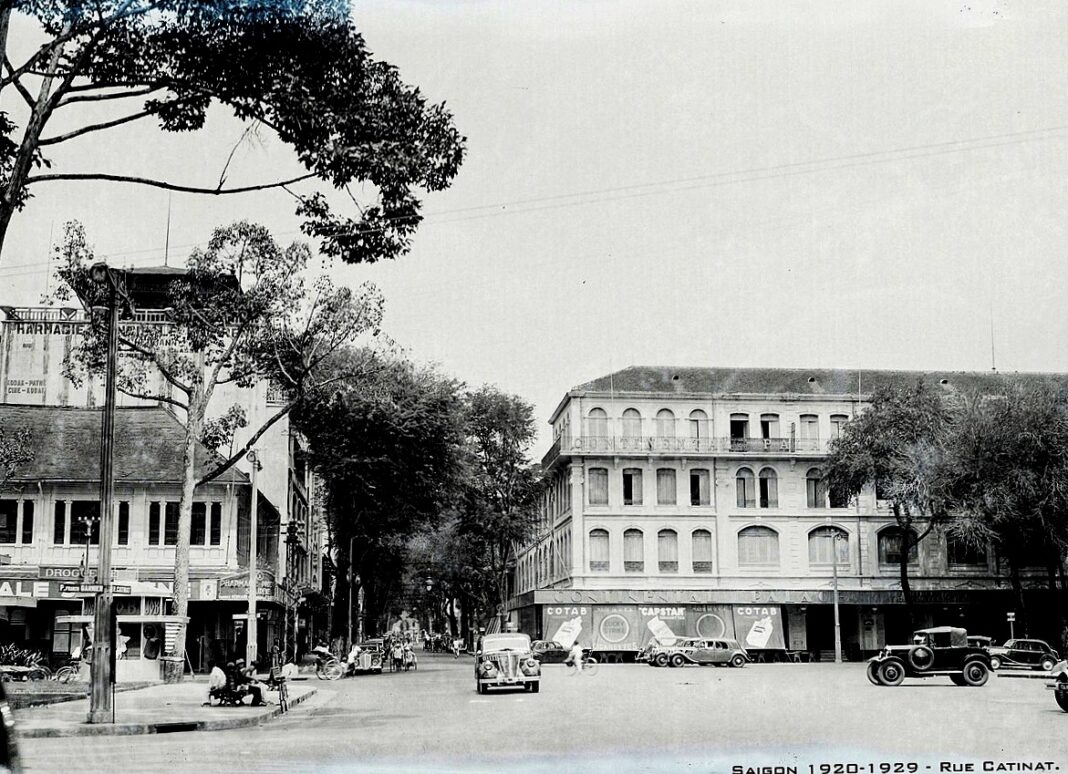

With its wide boulevards and sophisticated society, Saigon was known as “The Pearl of the Orient.” Life was grand in the capital of Indochina for those who chose to make the long journey from France, six weeks by boat. The city had hospitals, schools, trains and trams, and a postal service, all of course, French. Even justice was meted out French style, a guillotine and public executions took place in front of the Courthouse complex built in 1881, still standing imposingly next to the Independence Palace.

Walking around Saigon, one can easily find traces of its past everywhere, especially in its civic buildings, hospitals, and schools. The Post Office, Opera House, Archbishop’s Palace, City Hall, Ho Chi Mihn Museum, and Notre Dame Cathedral all showcase the might of France’s best architects. But there are some lesser-known fine colonial examples scattered all over the city.

Walking north of the Independence Palace down a leafy boulevard, one can find Chasseloup Laubat, the earliest and most prestigious education institution in Saigon, built in the 1870s. King Norodom of Cambodia, author Marguerite Duras, and many members of Lao royalty, including Prince Phetsarath and King Sisavangvong, received their education here. The original buildings, with their black and white tiled floors, wooden shutters, and tropical garden foliage, still function as a school. Round the corner from Chasseloup Laubat on Vo Van Tan Street, formerly Rue Testard, stands Marguerite’s home, now a bank, but you can still see its former glory beyond the smoked glass windows.

Ben Thanh Market (1914), Saigon’s social and geographical center, is probably the first stop for tourists searching for souvenirs, tee shirts, fridge magnets, and conical hats. Little has changed here apart from the merchandise and neon signs; it still has its clock and retains its original simple architecture. Don’t leave the market without taking a look across the street. In front stands the eye-catching Railway Office, built the same year, a much more elaborate example of colonial style with its mellow paint scheme, red-tiled roof, and swirly iron door panels. Once slated for demolition, this grand building has thankfully been spared the wrecking ball.

A good contemporary source on growing up in the colonies can be found in the works of French author Marguerite Duras. In her book The Lover, she talks about buying her famous fedora and diamanté cabaret shoes on sale at the Rue Catinat. The earliest grand avenue to be built, Rue Catinat, had everything the expat could want: cafes and bakeries selling French pastries and cheese, cinemas, and even a photography studio operated by an Algerian French man. Her mother spent some time playing piano at the Eden Cinema, which was demolished to make way for the Eden Center in 2009, directly across from the Continental Hotel.

With its elegant white façade and potted palms, the Continental was built in 1880 and is a fine example of French Colonial architecture with its proliferation of white arches and wrought iron railings. It is a good place to stop, sip a drink, and bask in the shady terraces and courtyard. Somerset Maugham was one guest who enjoyed a tipple here while reading the local newspapers. Graham Greene’s antiwar novel The Quiet American was written during one of his many visits. Set during the second Indochina War, a time of secrecy and intrigue, journalists and foreign correspondents ended up confined to the building during the worst battles for the city.

The splendid Central Post Office next to Notre Dame Cathedral, with its old wooden booths, is often attributed to Gustave Eiffel, but sadly, it is not his handiwork. To find a rare example of his skills, check the Pont des Messageries Maritimes, constructed in 1882. Teal-colored girders form a graceful crescent arch spanning the Arroyo Chinois. The bridge is pedestrian only and a popular local wedding photo and selfie spot, lit up at night.

The monumental Indochina Bank stands beside the bridge. This was the central bank of the colonies, where fresh piastres were minted and investments made in rubber plantations, rice production, and infrastructure. Its dark granite stonework combines elements of Art Deco, eastern, and colonial architecture into a potent mix.

Many of the avenues in central Saigon are lined with massive golden oak trees, some up to thirty meters tall, which make you feel positively Lilliputian in comparison. Almost twenty years have passed since my first visit to Saigon. I was worried that these magnificent giants planted 150 years ago would be victims of progress but there they are still growing upwards and thriving, much like Saigon.

ລາວ

ລາວ