Text by Vila Phounvongsa / Snaé History

Photos by Vila Phounvongsa

Translated by Jason Rolan

The Lao-Thai Friendship Bridge, which connects Vientiane, Laos, with Nong Khai, Thailand, was officially opened on April 8, 1994. Today, many Lao people consider this bridge the first Lao-Thai Friendship Bridge. But what if history tells us otherwise?

In fact, over 180 years ago, a remarkable wooden bridge was constructed across the mighty Mekong River—long before modern engineering existed. Imagine the scale of building such a structure with out today’s technology, spanning a river more than a kilometer wide. It’s difficult to fathom.

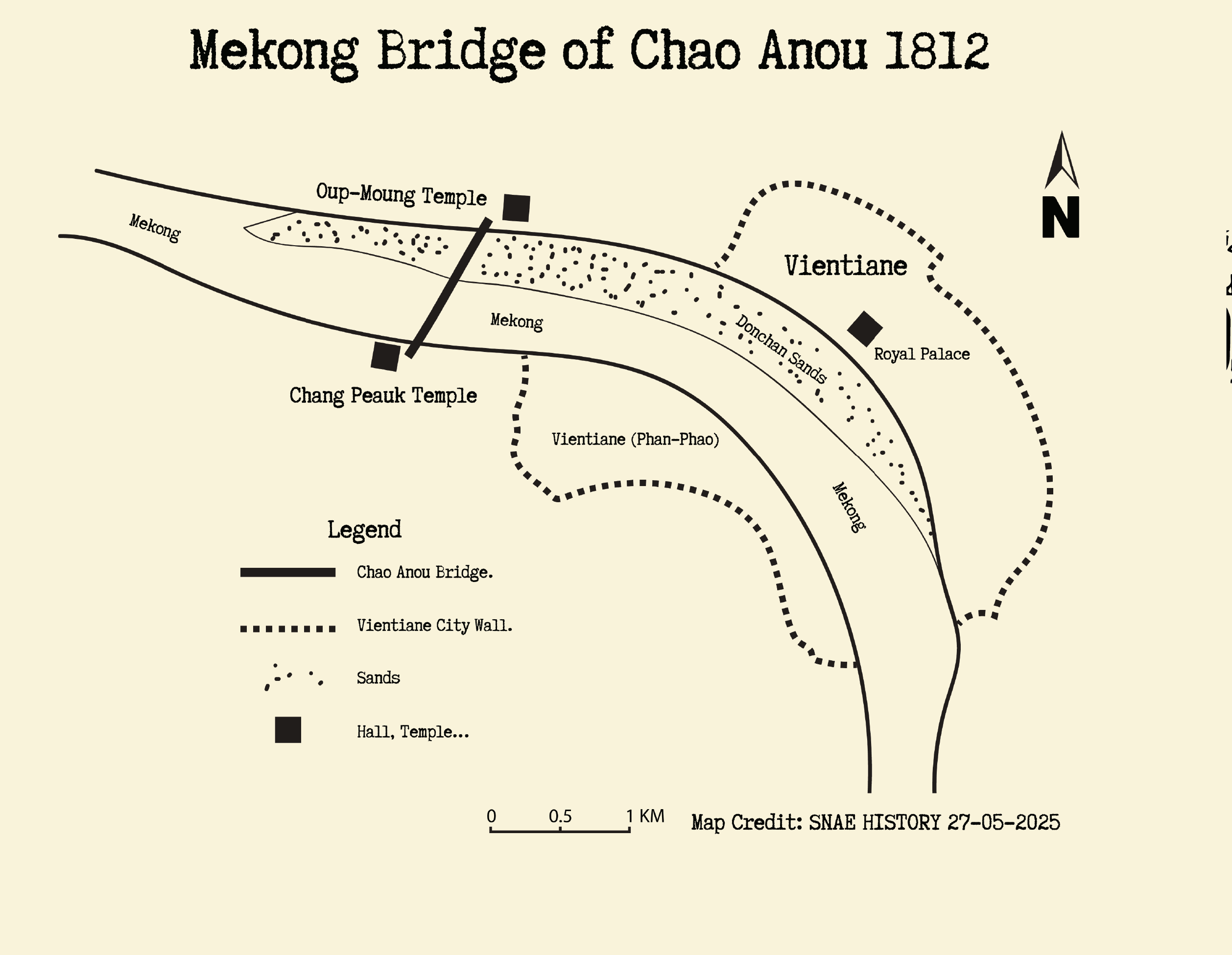

Back then, the Lane Xang Kingdom straddled both sides of the Mekong River. Rather than being a national border, the river was a lifeline for trade and movement. According to the Lao Chronicles, “Between 1810–1812, King Anouvong led the people to build a temple at Wat Chang Pheuak and a bridge across the Mekong at a point below the temple in Sri Chiang Mai village. The bridge connected to another temple, later known as Wat Oup Moung, and was used by Lao people living on both sides of the river.” The book 450 Years of Vientiane records that monks from 71 temples took part in the construction.

Lao historian Maha Sila Viravong also mentioned this wooden bridge in his book The Biography of King Anouvong:

“We cannot know exactly what kind of bridge he built. Stone carvings recount that he built a bridge to allow people to cross easily during celebrations at the Temple of the Emerald Buddha at Sri Chiang Mai village. I, the author, only saw a few remaining bridge pillars near Wat Oup Moung pier when the riverbank eroded in 1932. There were many. Villagers from Nong Panai dug them up and used them as parts for foot-powered rice pounders. The wood, even after being buried underwater for decades, remained strong. During April and May, when the Mekong receded, the remains were visible. Today, they can no longer be seen.”

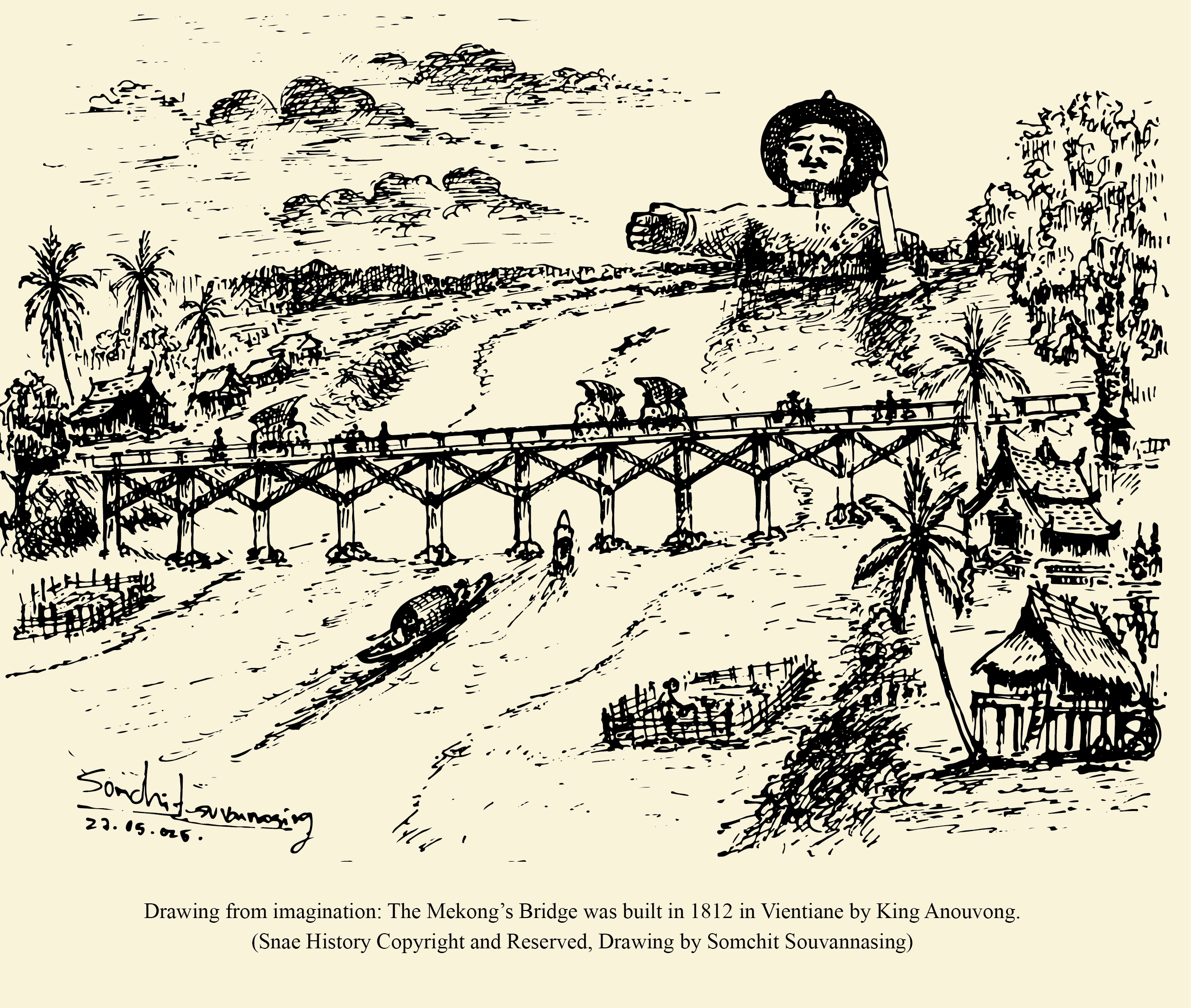

In Luang Prabang, a culture closely related to Vientiane, locals have long built seasonal wooden bridges across the Nam Khan River. These use tied wooden beams with stones stacked on their footings to withstand water flow. A central gap is left in some sections to allow boats to pass, and the walkways are made of tightly bound bamboo planks. These temporary bridges are used during the dry season for daily travel. In neighboring Myanmar, a more famous example is the U Bein Bridge—built between 1849–1851, over two decades after King Anouvong’s time. Spanning 1.2 km across Taungthaman Lake, the bridge was constructed using teak wood reclaimed from the old Ava Palace and remains the world’s oldest and longest teak bridge. As for the Mekong River bridge from King Anouvong’s reign, I, the author, explored the area in the summers of 2022 and 2025. While no wooden remains were visible, some clues still linger. I spoke with an elderly local who pointed to a large fig tree near the Oup Moung village spirit altar—now located behind the Eastin Hotel—as the spot where the bridge once began. He also recalled that during his childhood, villagers unearthed a massive wooden pillar believed to be part of the original bridge. Based on the surrounding geography, it is plausible that the bridge was constructed during the dry season, when a wide sandbar emerges, making such acrossing feasible. Based on the enviro-nmental clues and documentary sources, I believe the bridge likely resembled the wooden footbridges still found in Luang Prabang and Myanmar—made from hardwood tied together, anchored by stones, and including a gap for boat passage. Given the scale of the Mekong, the bridge was probably smaller than the U Bein Bridge and likely built for temporary use only during the dry season.

Its walkway might have been crafted from bamboo mats or poles tied across wooden planks. Of course, this is merely a hypothesis. The actual appearance and construction of the bridge remain unknown. We can only piece together fragments from the Lao chronicles and continue searching for physical remnants.

I leave the mystery with you, the reader. Perhaps one day, more evidence will emerge to help solve this intriguing puzzle from Laos’ past.

ລາວ

ລາວ